Bussakorn Binson

Introduction

Xylophones are found throughout southeast Asia, notably in Thailand, Cambodia, Indonesia, and with the Mon people of the Peguan region of southern Burma (Myanmar) and elsewhere in Burma. Thais believe (for example Yupho 1960: 12-14) that the ranaat (ระนาด) (a xylophone) evolved from the grap (กรับ). A grap is a 2 piece wooden clapper. The ranaat is comprised of series of suspended wooden bars, but the notes were coarse and out of tune. Originally they were then laid on two tracks or supports. Further improvements were made and the graps were constructed in different sizes and supported to allow the notes to resonate freely. To accomplish this, a heavy string was threaded through holes made near the ends of the graps. The graps were then placed close together and hung on a supporting stand. Two long, slender beaters with knobs at the end were used. The instrument could now be employed to play melodies. Further improvements were made to the shape of the grap, and a mixture of beeswax with lead shavings was applied to the underside of each one, permitting fine tuning and improving the tone. This original instrument was called a ranaat and the constituent graps were named luuk ranaat (ลูกระนาด). The full series of luuk ranaat were strung on the cord, forming a continuous flat surface which was called the phuun (ผืน). The luuk ranaat were made at first of two varieties of bamboo called phai bong (ไผ่บง) and phai tong (ไผ่ตง). Later, varieties of hard wood such as maichingchan (ไม้ชิงชัน), mai mahaat (ไม้มะหาด) and mai phayung (ไม้พะยูง), were used but phai bong was always preferred because of its beautiful tone. The supporting resonator had a shape similar to that of a Thai river boat, curving upwards at each end. This boat-shaped resonator was called the raang ranaat (รางระนาด). The two pieces which closes each end are called the khoon (โขน), literally referring to the headpiece or prow of a boat. This boat-shaped body rests on a squat, pyramid-shaped base, the bottom of which is approximately 22.5 cm (8.9”) square with a height of 8 cm (3.2”).

This base often had carved designs on it. In the first Thai musical ensembles only one ranaat was used, with fewer wooden bars than the modern model. Later on, another ranaat was devised to produce lower register. (The performing style was radically different from the first ranaat) This new model was called the ranaat thum (ระนาดทุ้ม) (low-pitched ranaat) and the original instrument which retained the higher notes was called the ranaat ek (ระนาดเอก) – first or principle ranaat (Figure 1 below)

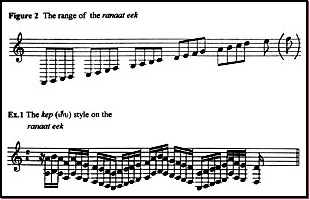

The traditional ranaat ek has 21 bars. The range is shown below (Figure 2). The final note in brackets is increasingly found on modern instruments. The lowest in pitch is 38 cm (15”) long, 5 cm (2”) wide and 1.5 cm (1/2”) thick. The bars decrease in size but become thicker as the pitch rises, All are hung on a cord which passes through holes at the nodes: 7.9 cm (2.75-3.5”)from the ends. The whole ‘keyboard,’ spanning about 120 cm (47.5”), is suspended over the boat-shaped body from two metal hooks inserted of the patterns in this thesis show the full range of the modern instrument. The majority, however, are conceived for the traditional 21-bar version. The player needs to know how to adapt the patterns which would naturally go beyond the range (at either and) of this instrument. Basically there are two options: transposition up or down one (or two) octaves; reducing the octave gap between the mallets.

It is worth noting that the range as shown in Figure 2 is a modern concept. The traditional range has the lowest note a fourth lower than its neighbor I.e. to play the lowest octave, the right mallet has tjo skip a fourth.

The ranaat ek player is a leader of the pii phaat (ปี่พาทย์) player – percussion ensemble, taking responsibility of performing the introduction to pieces and indication changes of tempo. The main playing style is a regular sequence of notes in octaves, known as kep (เก็บ). (Example 1)

Improvisation

Improvisation – kaan praaee tamnoong (การแปรทำนอง) in Thai music refers to the transformation of the basic melody according to the thaang (ทาง) performing way of each instrument. Improvisation in Thai music needs to be learnt and practiced and is totally involved with the process of memorization. This clearly conflicts with some Western concepts of the term: for examples, Michael Kennedy (1994: 428) writes : Improvisation (or extemporization) is performed according to the inventive whim of the moment, i.e. without a written or printed score, and not from memory.

Robina Backles Willson (1976: 189-190) also stated about improvisation in jazz:

As the jazzman improvised freely on the agreed harmonic basis of a tune, he not only produced cross rhythms with the other players, but also dissonant clashes.

Kennedy’s definition of improvisation, which rules out memorization, dose not adequately define the meaning in Thai music in which the memory plays an essential part in the process. Although there are some kinds of harmonic basis in Thai music, Willson’s mention of dissonant clashes is also inapplicable to Thai improvisation.

Mantle Hood (1975: 26) proposed a different definition of improvisation which allows for memorization, both as a mental process and a kinetic (muscular) one:

Improvisation cannot proceed without reference to memory both abstract and kinetic (muscular). It may or may not refer to sketches or manuscripts. From improvisation to improvisation the process of revision, polishing, and cultivation may take place without writing.

The differences between Thai and Western improvisation have been discussed by Ketukaenchan (1986 : 133) as follows:

…in Thai music, ‘improvisation’ is far less extensive and free than in some other types of music in which improvisation is generally recognized as having a major role to play. The Thai musician has to observe very strict rules, thus his ‘freedom’ is limited. At the same time this presents a special challenge to his imagination and skill.

The most important difference between Thai improvisation and western improvisation is that Thai improvisation is carefully controlled and regulated under the guidance of the director of the ensemble (the music master). Some pieces of music are arranged so that improvisation may not be carried out at all and each musician must memorize and play the exact music as arranged. This is the case in some types of composition such as the ‘phleeng thaang kroo’ (เพลงทางกรอ) – tremolo style, ‘phleeng luuk loo luuk khat’ (เพลงลูกล้อลูกขัด) – dialogue passages and the ‘pheeng naaphaat’ (เพลงหน้าพาทย์ ) – group of sacred music. In other cases, the thaang ranaat ek (ทางระนาดเอก) may be improvised freely in accordance with the performer’s skill but then the master in charge of the ensemble must always keep the unity of music. If the improvisation attempted by each musician begins to disrupt this unity, he or she will dictate the improvisational mode as a solution.

Before any attempt is made in improvisation, the student must first memorize many patterns. Next, the student will be taught the method of choosing the appropriate way to arrange the thaang patterns to fit each phrase of the piece. Improvisation on the ranaat ek can be learnt step by step as discussed below.

a) Imitation

Firstly, the student must learn how to fit various improvising patterns of the thaang ranaat ek into each phrase of the basic melody by observing and imitating the teacher. Then, the student must try to fit correctly each pattern to a phrase on his or her own; therefore through increasing experience, the greater variety of patterns evolves.

b) Arrangement

After understanding and recognizing all the patterns studied, the student tries to apply each pattern to fit different phrase of the basic melody, of find different patterns to the same phrase of the basic melody.

c) Spontaneous decisions - two main kinds may be distinguished:

1. Applying the thaang ranaat ek which has already been learned to the basic melody

2. Creating new patterns (during the performance). This skill can be acquired through the methods of practice outline below

Tii sap (ตีสับ) following the basic melody

The essence of learning improvisation is to proceed methodically from the very beginning. Firstly, the teacher explains the technique of tii sap: subdividing the regular notes of the main melody. The aim of this technique is to make the student familiar with the way of performing the fast regular notes which characterize the ranaat ek beating style, and to make both hands more stable before practicing the real thaang ranaat ek which involves leaps. The possible simplest first step is merely to beat each note of the main melody twice. (Examples 2 and 3).

Development of the tii sap technique

The basic tii sap technique is gradually transformed into something more closely resembling a real thaang ranaat ek by slight variations of a few notes. The important principle is that the change must be gradual, so that the student can fully absorb the process without rushing into complications (Examples 4 and 5). In Example 5, the bracketed section remains very close to the basic melody, while the beginning and the end attempt a more adventurous response.

Extensions to the tii sap technique

Improvising a phrase

After understanding the way of performing the regular note-patterns of the thaang kep, the student will then start improvising phrases which involve the technique of adding notes.

The technique of adding a few notes into the tii sap technique as described earlier can be the starting point for the beginner to understand clearly the way of improvisation. This is because after practicing the exercises of adding some notes, the student will become automatically used to the way of adding notes to each phrase, and then the understanding of the first level of improvisation will gradually be developed and improved.

Normally, the phrase of the basic melody is always repeated several times in each piece, hence, the more the student practices, the greater the variation of the thaang ranaat eed patterns will be discerned. The lessons of one piece, in which the student develops earlier exercises and imitates the example of adding notes to the tii sap technique, can be applied to another piece which uses a similar phrase

Ex. 2 Basic melody

Ex. 3 Tii sap on the thaang ranaat ek to fit Ex.2

Ex. 4 Basic melody

Ex. 5

Improvising a poetic phrase

The patterns of improvisation constantly apply to the poetic style such as kloon tai luot (กลอนไต่ลวด). kloon yoon takep (กลอบย้อนตะเข็บ), etc. The student must be very clear about the ways in which the different poetic phrases converge and diverge (examples 6-8).

Example 6 shows the shape of the kloon tai luot which is characterized by conjunct motion, both in ascent and descent.

Example 7 and 8 share the same overall undulating characteristic, but their beginnings are different. Moreover, each kloon (กลอน) or poetic style has a name which describes its motion, and this assists the student to memorize its musical features.

Difficulties in practising improvisation a) Restrictions of range

The patterns learnt for one piece can become problematic in another piece if the overall pitches are Different, because the transposition can take a pattern outside the range of the instrument. The same basic melody at different pitches, showing the adjustments necessary to keep within the range of the ranaat ek.

The transposed version of the thaang ranaat ek in Example 12 is unavailable because the notes indicated by * cannot be played on the instrument. A possible variant to take account of this problem would be:

b) Repetition

As already explained, the basic melody consists of various melodic patterns or phrases which sometimes appear many times in the same piece. Occasionally, a pattern can be repeated immediately; in other words, the basic melody may be played with the same phrase twice or more without any change. However, the ranaat ek must not repeat the same thaang to fit the basic melody, but must instead find variations. If two repeated phrases of thaang ranaat ek are not far apart, the repetition will create certain tedium, which should be avoided. The following examples show how the different possibilities of the thaang ranaat ek may be improvised to fit identical basic melodies. These two options can therefore be used to avoid the problem of repetition. It is important to note that the placing of each phrase depends on the characteristics and poetic styles (kloon) of adjacent phrases.

There are other interesting methods of Thai improvisation, which are not discussed in this article. Those interested can contact me. See my contact page.

Ex. 6 Kloon tai luot (กลอนไต่ลวด)

Ex. 7 Kloon yoon takep (กลอบย้อนตะเข็บ)

Ex. 8 Kloon doen takep (กลอนเดินตะเข็บ)

Ex. 9 Basic melody

Ex. 10 The thaang ranaat ek to fit this could be

Ex. 11 Basic melody, transposed upwards

Ex. 12

Ex. 13

Ex. 14 The same phrase repeated

Ex. 15 Possibility #1

Ex. 16 Possibility #2

Glossary of the important Thai terms

Grap (กรับ) wooden clappers

Kep (เก็บ) regular stream of fast notes Played in octaves on the Ranaat ek

Khoon (โขน) the two pieces which close each end of the raang ranaat

kloon (กลอน) phrases played against the basic melody, arranged in symmetrically balanced phrases (poetic style). Most kloon for the ranaat ek now have names, but some others have not yet been named.

Kloon doen takhep (กลอนเดินตะเข็บ) Kloon with sequential repetition of the initial four note motif

Kloon tai luot (กลอนไต่ลวด) Kloon characterized by conjunct motion

Kloon yoon takhep (กลอนย้อนตะเข็บ) Kloon in which the pattern is similar to that of kloon doen takhep but in a different shape

Kroo (กรอ) the technique of playing sustained notes by means of tremolo

Luuk ranaat (ลูกระนาด) Bar of the ranaat

Mai (ไม้) wood

Phleeng (เพลง) a piece/composition

Phuun (ผืน) set of bars of the ranaat Pii (»Õè) reed instrument

Pii phaat (ปี่พาทย์) Percussion ensemble

Raang ranaat (รางระนาด) The principal Thai xylophone with 21 keys, usually playing in octaves and responsible for performing the introduction to pieces

Thaang (ทาง) path or way. The pattern(s) of a particular instrument, or style of a master.

Thaang ranaat ek (ทางระนาดเอก) A way of performing on the ranaat ek

References In English

- Duriyanga, Chen, Phra. 1948. Siamese Music in Theory and Practice as Compared with that of the West and a Description of the Riphat. Bangkok: Department of Fine Arts.

- Hood, Mantle. 1975. Improvisation in the Stratified Ensembles of S.E. Asia, Selected Readings in Ethnomusicology 2:25-33.

- Kennedy, Michael. 1994. The Oxford Dictionary of Music, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Ketukaenchan, Somsak. 1989. The thang of the knong wong yai and ranat ek: A Transcription and Analysis of Performance Practice in Thai Music. Unpublished D Phil. Thesis, University of York.

- Silkstone, Francis. 1993. Learning Thai Classical Music: Memorization and Improvisation. Unpublished D Phil. Thesis, School of Oriental and African Studies, Centre of Music Studies, University of London.

- Willson, Robinal Bechles. 1976. The Voice of Music, London: Morrison & Gibb.

- Yupho, Dhanit 1960. Thai Musical Instruments 1st edition, trans. David Morton, Bangkok: Department of Fine Arts. (In Thai)

- Sumrongthong, Bussakorn. 1996. Kaankamnoed thamnoong khoong khrung dontrii damnoen thamnoong prapheet khrueng tii [Improvisation in Thai melodic percussion] Bangkok: Chulalongkorn University Press.

- Thavorn, Prasit. 1979. ‘Luk sip prakarn’ [Ten Principles, in Dontrii Thai Udomsuksa [Thai music in University] no. 8., Dangkok: Ramkhumhaeng University.

- Tramote, Montri. 1964. Sap Sangkhiit [Dictionary of Thai musical terms], Bangkok: Department of Fine Arts.