|

|

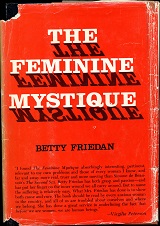

- "Betty

Friedan (1921–2006)," National Women's History Museum

Women's rights leader and activist Betty Freidan was born in

1921 to Russian Jewish immigrants. A summa cum laude graduate

of Smith College in 1942, Friedan trained as a psychologist at

University of California, Berkeley, but became a suburban

housewife and mother in New York, supplementing her husband’s

income by writing freelance articles for women’s magazines.

- "Betty

Friedan Interview," The First Measured Century,

PBS

QUESTION: And that's where your children grew up?

BETTY FRIEDAN: So my children, yes, they grew up in Rockland

County, and I wrote my book, The Feminine Mystique.

And after I was fired for being pregnant, I was technically a

housewife. And it was the era that I later analyzed, the

"feminine mystique" era, [when] "career woman" was a dirty

word. And so I didn't want a career anymore. [But] I had to do

something. So I started freelancing for women's magazines.

And then I was asked to do a questionnaire of the alumni

reunion at Smith, 15 years after we graduated, so this would

have been 1957. And I, after all, had had some training with

questionnaires [as a] psychologist, and as a reporter. But I

put entirely too much work in this questionnaire, [and] I

decided I'd make an article. I wrote for the women's magazine

and [for] McCall's, Redbook, Ladies Home

Journal.

There had been a book out called Modern Woman, the Lost

Sex, which said [that] too much education was making

American women frustrated in their roles as women, and they

would readjust to their role as women. But I believed in

education for women so I thought I'd disprove this with my

questionnaire. But, of course, my questionnaire didn't

disprove that. But it showed that with all the education,

American women were frustrated in just the role of

housewife—but they also managed to enlarge it. And they

weren't just housewives, they were community leaders, at least

the Smith graduates were. But whatever I wrote was heretical.

It offended the editors of the women's magazines. So after I

had about four versions of it turned down, I said, "Hey,

what's going on here?" Because I had never had an article

turned down. And I realized that what I was saying was

threatening, somehow, to the editors of these women's

magazines. That it threatened the very world they were trying

to paint, what I then called the "feminine mystique." And I

would have to write it as a book, because I wasn't going to

get it in a magazine. And the rest is history.

- Louis Menand, "Books

as Bombs: Why the Women's Movement Needed The Feminine

Mystique," The New Yorker 24 Jan. 2011.

When Friedan was writing her book, the issue of gender

equality was barely on the public’s radar screen. On the

contrary: it was almost taken for granted that the proper goal

for intelligent women was marriage—even by the presidents of

women’s colleges. Coontz quotes the president of Radcliffe

suggesting that if a Radcliffe graduate was really lucky she

might end up marrying a Harvard man. Friedan quoted the

president of Mills College citing with approval the remark

“Women should be educated so that they can argue with their

husbands.”

- Emily Bazelon, "The

Feminine Mystique at 50," Slate (2013)

[...] in her masterful introduction to this 50th-anniversary

edition we are reading, Gail Collins says that “if you want to

understand what has happened to American women over the last

half-century, their extraordinary journey from Doris Day to

Buffy the Vampire Slayer and beyond, you have to start with

this book.” She’s exactly right. Here’s one tiny example: In

the book, Betty recounts giving up a fellowship she won after

graduating from Smith, which would have supported her in

getting a Ph.D. in psychology, because a boy she liked said

their relationship would have to end since he’d never win a

fellowship like hers. She writes, “I gave up the fellowship,

in relief.” What? In relief? This is inconceivable to

me. I don’t mean compromising one’s career goal for love,

which I’ve done, but giving up a plum opportunity because of a

guy’s insecurity—that is not in my universe. And that shift

captures much of the power of this book, right? For

middle-class American women, it changed the whole deal—the

aspirations we felt we could have and the reception we

expected for them.

- Betty Friedan, "The

Problem That Has No Name," The Feminine Mystique

(New York: Norton, 1963)

|