Faculty of Arts,

Chulalongkorn University

Story of Your Life

(1998)

Ted

Chiang

(1967 – )

Notes

"Story of Your

Life" first appeared in the collection Starlight

2 in 1998.

112 Colonel

Weber, I presume?: allusion to the famous greeting that Henry Morton

Stanley gives David Livingstone: "Doctor Livingstone, I presume?" upon

finding him in the town of Ujiji (now a part of Tanzania) after a lengthy

search expedition

Stanley and Livingstone,

dir. Henry King and Otto Brower (1939)

A supercut of the phrase being

referenced in various performances

|

- "Dr.

Livingstone, I Presume?," QI: Quite Interesting

‘Dr Livingstone, I presume?’ is one of the most famous quotes

in history and was supposedly uttered by the explorer Henry

Morton Stanley in 1871 upon finding the missing missionary

David Livingstone. However, the quote is now believed to have

been invented by Stanley or his biographer. Stanley’s diary

pages referring to the encounter were torn out and

Livingstone’s account of the meeting doesn’t mention the

phrase.

- Leslie Dunkling, "Quotation

Vocatives," A Dictionary of Epithets and Terms of

Address (London: Routledge, 2006)

Transferred vocatives are usually names. A person who

expresses surprise at someone's deductive powers is told that

it is 'Elementary, my dear Watson'. A meeting in certain

circumstances inspires the use of 'Dr Livingstone, I presume'.

- Andrew Delahunty and Sheila Dignen, "Stanley,

Sir Henry Morton," A Dictionary of Reference and

Allusion, 3rd ed. (Oxford: OUP, 2012): 341

The Welsh explorer and journalist who, sent by the New

York Herald, 'found' Dr Livingstone at Ujiji in 1871,

and, according to the popular account, greeted him with the

words 'Doctor Livingstone, I presume?'.

➢ Someone who eventually finds another after much searching

- Eric Partridge, "Doctor

Livingstone, I presume," A Dictionary of Catch

Phrases British and American, from the Sixteenth Century to

the Present Day, ed. Paul Beale (London: Routledge,

2003): 101

is both a very famous quotation and a remarkably persistent

catch phrase; the words were spoken in 1871 by Henry Morton,

later Sir Henry, Stanley (1841–1904), when he, a journalist,

at last came up with David Livingstone (1813–73) in Central

Africa. Livingstone, physician, missionary, explorer, was

thought to be lost

- Martin Dugard, "Stanley Meets Livingstone," Smithsonian

(2003)

[...]

What Stanley saw was a pale white man wearing a faded blue cap

and patched clothing. The man’s hair was white, he had few

teeth, and his beard was bushy. He walked, Stanley wrote,

“with a firm and heavy tread.”

Stanley stepped up crisply to the old man, removed his helmet

and extended his hand. According to Stanley’s journal, it was

November 10, 1871. With formal intonation, representing

America but trying to affect British gravity, Stanley spoke,

according to later accounts, the most dignified words that

came to mind: “Dr. Livingstone, I presume?”

“Yes,” Livingstone answered simply.

“I thank God, doctor,” Stanley said, appalled at how fragile

Livingstone looked, “I have been permitted to see you.”

“I feel thankful,” Livingstone said with typical

understatement, “I am here to welcome you.”

|

156 Borgesian

fabulation: a story like those by the Argentine author Jorge Luis

Borges

163 that

famous optical illusion: the ambiguous figure often called the

Boring figure after Edwin G. Boring who wrote about it in a psychology

journal article in 1930.

Edwin G. Boring, "An Ambiguous

Figure," The American Journal of Psychology 42.3 (1930):

444.

|

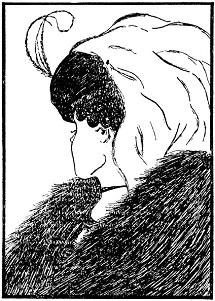

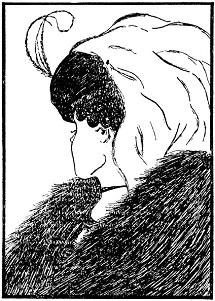

- Edwin G. Boring, "A

New Ambiguous Figure," The American Journal of

Psychology 42.3 (1930): 444–45.

The picture presented herewith is not strictly new. It was

drawn by the well-known cartoonist, W. E. Hill, and reproduced

in the issue of Puck for the week ending November 6, 1915. It

is, however, relatively unknown to psy- [end of page 444]

chologists, and seems to me to be the best of the

puzzle-pictures in the sense that neither figure is favored

over the other. [...] The present cut is from a pen-and-ink

copy of Hill's published half-tone. I am indebted to Mrs. W.

H. Hunt for the copy, which is, if anything, a little better

for the psychologist's use than the original.

This picture was originally published under the title "My Wife

and My Mother-in-law." It shows in one figure the left profile

of a young woman, three quarters from behind. The other figure

is an old woman, three-quarters from in front. The ear of the

'wife' is the left eye of the 'mother-in-law'; the left

eye-lash of the former is the right eye-lash of the latter;

the jaw of the former is the nose of the latter; the

neck-ribbon of the former, the mouth of the latter.

|

Story

Notes

This story grew out of my interest

in the variational principles of physics. I’ve found these principles

fascinating ever since I first learned of them, but I didn’t know how to

use them in a story until I saw a performance of Time Flies When

You’re Alive, Paul Linke’s one-man show about his wife’s battle with

[end of page 333] breast cancer. It occurred to me then that I might be

able to use variational principles to tell a story about a person’s

response to the inevitable. A few years later, that notion combined with a

friend’s remark about her newborn baby to form the nucleus of this story.

For those

interested in physics, I should note that the story’s discussion of

Fermat’s Principle of Least Time omits all mention of its

quantum-mechanical underpinnings. The QM formulation is interesting in its

own way, but I preferred the metaphoric possibilities of the classical

version.

As for this story’s

theme, probably the most concise summation of it that I’ve seen appears in

Kurt Vonnegut’s introduction to the 25th anniversary edition of Slaughterhouse-Five:

‘Stephen Hawking...found it tantalizing that we could not remember the

future. But remembering the future is child’s play for me now. I know what

will become of my helpless, trusting babies because they are grown-ups

now. I know how my closest friends will end up because so many of them are

retired or dead now...To Stephen Hawking and all others younger than

myself I say, “Be patient. Your future will come to you and lie down at

your feet like a dog who knows and loves you no matter what you are.”’

—Ted

Chiang, "Story

Notes," Stories of Your Life and

Others, Picador, 2015, pp. 333–34.

Understand

My new language is taking shape.

It is gestalt-oriented, rendering it beautifully suited for thought, but

impractical for writing or speech. It wouldn't be transcribed in the form

of words arranged linearly, but as a giant ideogram, to be absorbed as a

whole. Such an ideogram could convey, more deliberately than a picture,

what a thousand words cannot. The intricacy of each ideogram would be

commensurate with the amount of information contained; I amuse myself with

the notion of a colossal ideogram that describes the entire universe.

The printed page is too clumsy and

static for this language; the only serviceable media would be video or

holo, displaying a time-evolving graphic image. Speaking this language

would be out of the question, given the limited bandwidth of the human

larynx. (63)

—Ted Chiang, "Understand," 1991, Stories

of Your Life and Others (London: Picador, 2015): 37–84.

|

Comprehension Check

- What does the expression to ask

the question or to pop the question usually mean? What is

the question that "your father is about to ask me" (111)?

- Why will the narrator and her

child "never get that chance" of sharing the story of "the

night you're conceived" (111)?

- What does the phone call from

"Mountain Rescue" suggest about how and where the daughter

died (115)?

- When Louise Banks describes her

moose call as "Sends them running," who or what does "them"

refer to (120)?

- What does the daughter's

declaration "'I get the feeling it’s going to be a scorcher.

Good thing you’re dressed for it, Mom'" reveal about Louise

Banks' outfit that date night (124)?

|

|

Study Questions

- Why are the "alien devices"

called "looking glasses" (116)?

- How does Chiang approximate

Heptapod B-like simultaneity in telling the story with

English which is a sequential language?

- How does the description of the

heptapods' physical radial symmetry (117–8) relate to the

later descriptions of their spoken and written language (ex.

127–29, 132, 137, 145–47)?

- In the Arrival San

Diego premiere hosted by the Arthur C. Clarke Center for

Human Imagination Q

and A session with Ted Chiang, he mentions several

times the "emotional core" of the story that he hoped would

survive adaptation into film (ex. at 20:30–21:20 min.). What

do you think this emotional core of the story is?

|

Review Sheet

Characters

Louise Banks, the narrator – "Right now your dad and I have been

married for about two years" (111); "Louise Banks" (112); "with training

in field linguistics" (114)

Gary Donnelly – physicist (113); "easily identifiable as

an academic: full beard and mustache, wearing corduroy" (112)

You – "the scenario of your origin you'll

suggest when you're twelve. 'The only reason you had me was so you could

get a maid you wouldn't have to pay'" (111); "You'll be six when your

father has a conference to attend in Hawaii" (133); "a grown woman taller

than me and beautiful enough to make my heart ache" (135); "after

graduation, you'll be heading for a job as a financial analyst" (135);

"Your eyes will be blue like your dad's, not mud brown like mine [...] You

will have many suitors" (144);

Colonel Weber

– "wore a military uniform and a crew

cut, and carried an aluminum briefcase" (112)

Nelson – "By then Nelson and I will have moved

into our farmhouse" (112); "Nelson is ruggedly handsome, to your

evident approval" (124)

Flapper – "I dubbed them Flapper and

Raspberry" (125)

Raspberry – "Raspberry began

mimicking Gary [...] while Flapper worked their computer"

(126); "Raspberry left the room and returned with some

kind of giant nut" (126)

Vocabulary

plot

conflict

setting

character; characterization

protagonist

point of view; perspective

internal

diction

pace

imagery

movement

trajectory

metaphor

simile

symbol(s);

symbolism; symbolic

irony; ironic

contrast

structure

frame(s);

framing

relativism

internalization

essentialization

theme(s)

family

parenting; parent-child relationship

language

language

learning

knowledge

memory;

remembrance

expectation(s)

predestination

agency

free

will

time;

past; present; future

space

pain

grief

mourning

joy

love

life

death

alien;

extraterrestrial life

alien

invasion

science

the

military

politics

communication

linguistics

language

thought

worldview

simultaneity

linearity;

nonlinearity

chronology,

chronological

pattern(s)

genre(s)

science

fiction

speculative

fiction

Sample

Student

Responses to Ted Chiang's "Story of Your Life"

Response

1::

|

|

Ticha Wanichtamrong

2202235 Reading and Analysis in the Study

of English Literature

Acharn Puckpan Tipayamontri

April 23, 2016

Reading Response 3

Title

Text.

|

|

Reference

| Media |

|

- "Speculative Visions with Ted Chiang,"

Asian American Writers' Workshop (2016; 1 hr. 21:44 min.;

Chiang reads new work; Q and A begins at 25:30)

|

|

- "Arrival Premiere with Writer

Ted Chiang," Arthur C. Clarke Center for Human Imagination

(2016; 1 hr. 1:22 min.)

|

|

- "Arrival Trailer," Paramount

Pictures (2016; 2:25 min.)

|

Ted

Chiang

|

- "Summary

Bibliography: Ted Chiang," Internet Speculative

Fiction Database

- Interviews

- Joshua Rothman, "Ted

Chiang's Soulful Science Fiction," The New

Yorker (2017)

- Meghan McCarron, "The

Legendary Ted Chiang on Seeing His Stories Adapted

and the Ever-Expanding Popularity of SF,"

Electric Literature (2016)

- Taylor Clark, "The

Perfectionist," The California Sunday Magazine

(2015)

- Avi Solomon, "Ted

Chiang on Writing," Boing Boing (2010)

- Lou Anders, "A

Conversation with Ted Chiang," SF Site (2002)

- Jeremy Smith, "The

Absence of God: An Interview with Ted Chiang,"

Infinity Plus (2002)

|

Reference

Chiang, Ted. “Story of Your Life.” 1998. Stories

of Your Life and Others, Picador, 2015, pp. 111–72.

Further

Reading

Chiang, Ted. Stories of Your Life and

Others. Picador, 2015.

Chiang, Ted, and Allora and Calzadilla. "The

Great Silence." Fantasy and Science Fiction , vol. 130,

no. 5/6, 2016, pp. 134–38.

Chiang, Ted. "The

Truth of Fact, the Truth of Feeling." Subterranean Press

Magazine (fall 2013).

Home | Literary

Terms | English Help

Last updated March 12, 2019