- Franz Kafka, Wordsworth Editions (biography)

- "A Report for an Academy" (1917)

- "A Report for an Academy," trans. Ian Johnston (2015)

- "A Report to an Academy," trans. Tania and James Stern, The Kafka Project

Franz Kafka, 1917

Department of English

Faculty of Arts, Chulalongkorn University

We Are Completely Beside Ourselves

(2014)

Karen Joy Fowler

(1950 – )

| |

|

Notes

Franz Kafka:

|

Franz Kafka, 1917 |

11 Jean Harlow:

Jean Harlow, 1935 |

|

200 lived the life of Riley: an American expression meaning to live the good life, without hard work or worries

283 baby books:

A Conversation With Karen Joy Fowler

Q: This

book was inspired in part by a real-life experiment in the 1930s, in

which two scientists, a husband-and-wife team, tried to raise a baby

chimpanzee in their home as if she were human, along with their own

child. That experiment didn’t last long; there was a rumor that their

infant son soon began adopting chimp behaviors. Your own father, like

the psychologist father in your novel, was an Indiana University

professor who studied animal behavior. But it was your daughter who

raised the question that became the seed for this novel. How did all

these pieces come together for you?

Fowler: I began arguing with my

father about animal intelligence when I was about six years old. His

conclusions were based on a career of cautious, scientifically collected

data; mine were based on my personal observations of the family dogs and

cats, birds and rats. You might have thought that I would have developed

some humility at some point, bowed to his greater expertise. But that just

shows how little you know me.

In many ways, this book represents my latest salvo in that long-running argument. I deeply regret that my father is no longer here to answer back. I deeply regret that he didn’t live to see my daughter’s work on the development of diving and foraging behaviors in sea lions. The family is rich in animal behaviorists. Also in teachers, arguably much the same thing.

Q: How many

accounts are there of chimps being raised like human babies? How

closely did you base your story on these accounts?

Fowler: When I began thinking

about the book, I was intimidated by how little I knew about chimps; I

consoled myself that I did know quite a lot about psychologists. So I read

all the accounts of cross-fostered chimps that I could find and, yes,

there are several of these. Many of them are referenced in my novel: The

Ape and the Child is about the Kelloggs. Next of Kin is about Washoe. Viki

Hayes is The Ape in Our House. The Chimp Who Would Be Human is Nim

Chimpsky. There is a very disturbing book by Maurice Temerlin called Lucy:

Growing Up Human. I read a ton of other stuff as well, about chimps and

bonobos in labs, in the wild, on preserves. I know I’m pushing the limits

in many ways, but I wanted Fern’s behaviors to be as plausible as I could

make them, so I depended on these non-fiction accounts. I also took a

“chimposeum” at the Chimpanzee and Human Communication Institute in

Ellensburg, Washington and got to observe the chimps in residence there.

Q: Why do you

begin this story in the middle?

Fowler: The short answer is that

there was no other way Rosemary, my narrator, could have told it.

The longer answer is found in a point her brother Lowell makes when he

talks to her about their father’s work. Lowell complains that their

father, in his careful, scientific way, started by assuming Fern’s

difference from humans. This put the onus on Fern to prove herself at

every point. Lowell says it would have been just as careful and scientific

to start at the other end, assume Fern’s similarities to human children

and demand the proof of difference. It would have been more Darwinian, he

says, to start with an assumption of kinship.

I wanted the book to start with the assumption of kinship in that same

way. I wanted the reader to assume the similarities, before looking for

the differences. In order to accomplish that, I felt I had to talk about

Fern first as a sister and only later as a chimpanzee.

Q: What is

Rosemary’s father, a university professor of psychology, hoping to

accomplish by raising Fern with his own children? What is the role

of Rosemary’s mother in the story?

Fowler: Since Rosemary remains

uncertain of her father’s goals, I too remain uncertain of her father’s

goals.

Ostensibly it was an experiment in nature vs nurture – what would Fern be

capable of if she were raised as human, especially in the area of

language? But as the daughter of a psychologist, I can tell you that the

thing ostensibly being studied is never the thing being studied. Rosemary

suspects that she and not Fern was the real subject of the experiment –

that her father was not trying to raise a chimp who could talk to humans,

but rather a human who could talk to chimps. But Rosemary is very angry at

her father when she thinks this and she is probably being unfair.

Probably.

Rosemary’s mother was an equal partner in the experiment though Rosemary

is reluctant to admit this, feeling protective and defensive in the face

of her mother’s complete collapse.

Q: As Rosemary

ponders her relationship with Fern, she wonders whether the

experiment of raising them together reveals more about the nature of

humans than the nature of chimps. How so? In what ways is Fern more

advanced than Rosemary in their earliest years?

Fowler: As I researched these

experiments, I was struck by how long it took for someone to note that, if

we were interested in chimps and communication, it was more relevant to

ask how they communicated with each other than how well they could learn

to communicate with us. To remove the human from the center of these

“chimp experiments” took about a century. In all that time there was

little to suggest that the fault might be ours for not understanding

rather than theirs for not making us understand. The primacy of the human

and the priority given to human forms of intelligence and communication

was largely unquestioned.

Chimps develop much more quickly than humans and, until around the age of

two, are more advanced in every conceivable way.

Q: In school,

Rosemary is taunted by her classmates for being a “monkey girl,” but

in fact she herself realizes that she has unconsciously taken on

certain chimp traits. What are some of these?

Fowler: The classic chimp traits

she attributes to herself are outlined on her kindergarten report card

where she is described as impulsive, possessive, and demanding. She has a

hard time keeping her hands to herself and she tends to see the space

around her vertically as well as horizontally. Although she cannot climb

the way her sister Fern does, she sees the world as climbable.

Q: Rosemary’s

brother, Lowell, becomes an animal rights activist in response to

losing Fern. He takes part in several illegal actions to liberate

animals and is hunted by the police. What do you think of the animal

rights movement as a whole, and of the small part of it that

participates in such actions?

Fowler: I think these are very

hard questions to answer and I hope my novel represents my own complicated

feelings better than a more reductive answer here will do. I believe in

science and in medical research. I eat meat. But I also believe that our

food industries as well as our animal research facilities, not to even

mention cosmetics, involve redundant and indefensible cruelties. The idea

of animals raised only to lives of utter misery is a horrifying one.

I guess what I believe is that things should be done in the open. If we

can’t bear to look at what we are doing, then we shouldn’t be doing it. Of

course, this precept reaches far beyond our relationship with our fellow

animals into our politics, our environmental policies, our wars, and our

prisons. A lot of what the animal rights activists do is simply make us

look. I’m all in favor of that.

Q: What does the

knowledge about chimps that Rosemary gains in college reveal about

human gender relations, patriarchy, religion, and violence?

Fowler: Nothing revealed, many

things suggested. The differences between chimps and bonobos in these

areas are stark and we share approximately the same percentage of DNA with

both. Plus our understanding of both is continually evolving. But it is

instructive from time to time to remember that humans are primates and to

view our behaviors through that lens. Look around at our hierarchical

institutions – the boardrooms, the diocese, our town halls, and

bureaucracies. You’ll see lot of posturing and chest-thumping, a stylized

tango of dominance displays. I agree with Rosemary’s father when he says

that the only way to make sense of the US Congress is to look at it as a

200-year primate study.

Q: Rosemary’s

experiences with Fern raise a number of philosophical and

psychological issues that go to the heart of what it means to be

human, or so it was traditionally thought – issues like solipsism,

theory of mind, and episodic memory. Can you elaborate on this a

little?

Fowler: It seems to me that every

time we think we’ve narrowed in on what the crucial difference between

humans and the rest of the animals is, we turn out to be wrong again. I

remember when man was the tool-using animal. Now we know that many animals

use tools. Chimps have a theory of mind. Scrub jays evidence episodic

memory. We have underestimated our fellow animals at every turn, mainly by

being unable to see beyond ourselves. It would be nice if we could stop

doing that.

Q: Fern, like

other chimps, is able to use sign language at quite a high level,

although she cannot speak, while Rosemary speaks a lot as a child,

but goes relatively silent in her adolescence. What role does

language and talking play in this novel?

Fowler: Whether any chimp has used

sign language at a high level is still controversial. Fern has a decent

vocabulary, but that’s different from being able to communicate complex

matters. She and Rosemary appear to understand each other quite well, but

how much of that comes from Fern and how much is Rosemary imposing and

imagining Fern’s side of the communication is also an open question.

I conceived of the novel as being all about language, who talks and who

doesn’t. Who is heard and who isn’t. What can be said and by whom, and

what can’t be. As a young child, Rosemary believed her talking was

valuable so she did a lot of it. When Fern is sent off, Rosemary learns it

isn’t valuable; she learns to be silent. But by the end of the novel, her

ability to talk is important again, crucial, in fact, as her brother and

her sister need their story told and Rosemary is the only one who can do

this.

Q: Heartbreakingly,

Fern has to live under terrible conditions for many years after she

is taken away from the Cookes. Have living conditions for chimps in

institutions improved in recent years? Are there adequate facilities

for them all?

Fowler: There are an estimated

2000 chimpanzees living in the US today, in labs, in zoos, in homes, in

sanctuaries. I would say there’s been a great movement toward improvement

overall, but individually their circumstances vary greatly. There are now

a number of organizations dedicated to finding appropriate care and space

for those chimps retired from the labs and entertainment industry, but

this is an expensive endeavor. The sanctuaries are always at capacity.

Plus those chimpanzees who’ve been taken early from their mothers and

raised in largely human environments or in isolation, will find joining

chimp society to be difficult at best.

Public awareness and public donations are critical. Nim Chimpsky was saved

from the medical labs by a public outcry. Also the astronaut chimps.

A great place to donate money is Save the Chimps, which appears to be a

very effective organization dealing with exactly this. CNN did a show last

year on their careful, decade-long relocation of the chimps from the

Coulston Foundation (shut down after three of their chimpanzees died when

the heat in their cages hit 140 degrees) to a sanctuary in Florida.

Q: In 2011, as

you write, the National Institutes of Health changed its policy

toward the use of chimps in medical and behavioral experiments. From

now on, the NIH will support only those very few chimp studies that

are absolutely necessary for human health, and that can be conducted

in no other way. How will this change the situation of chimps in

this country?

Fowler: This is excellent news

(the US was one of only two countries in the world still using chimps in

experiments) as long as good homes can be found for the retired research

subjects. There is, of course, a shortfall in the money needed to relocate

these chimps to sanctuaries. It looks possible that many will have to stay

at the labs even as the experiments (and grant money) come to an end.

Q: There have

been a number of incidents in recent years in which chimps have

attacked humans, most notably the one in Connecticut where a woman

lost her face and hands. Can chimps really live closely with people

in the long term? Is it cruel to socialize them with humans when

they will eventually have to be moved into a different environment,

as they grow bigger and stronger?

Fowler: Chimps are extremely

dangerous animals, particularly the males. They can be managed as

children, but when they hit adolescence, they are so very much stronger

than humans, they can no longer be controlled. So no, they cannot live

with people over the long term and yes, it is cruel to raise them as

humans. They live for about 50 years in captivity and they become

uncontrollable at 10 or earlier. For most of their lives then, living with

humans is not going to be an option. They should be left with their

mothers.

Q: What is the

situation of chimps in the wild in Africa? Are their numbers

increasing or decreasing? What are their long-range prospects?

Fowler: Chimps suffer from the

same habitat encroachment as every other wild animal. Their populations

have declined by 66% in the last 30 years and both the common chimp and

the bonobo are classified as endangered.

Q: The epigraphs

throughout your novel are taken from a short story by Franz Kafka

called “A Report for an Academy,” whose narrator is an ape. How did

this story inform your own?

Fowler: Kafka’s story is about a

captive ape who must learn to behave as human in order to win for himself

some small measure of freedom. It is a flexible story as most of our

stories with animal characters are. What is Black Beauty about? Horses?

Slaves? Women? This is an intriguing part of the puzzle, the tangle of our

relationship to other animals, that so much of our literature, especially

that aimed at children (which Kafka’s story certainly is not) involves

talking animals. The Wind in the Willows, Charlotte’s Web, Winnie the Pooh

– these are all books my parents read to me as a child and I still hear my

father’s voice in Roo and Templeton and Toad. As children we are

encouraged to feel a great sympathy for animals and then expected to cast

that off as part of growing up.

Except that these animal characters are not really animals at all. It is

unlikely that Kafka was actually writing about apes in “Report to an

Academy.” But the story is too pertinent to my purposes not to ignore the

metaphor.

Q: What do you

hope readers take away from this novel?

Fowler: A century ago the

anti-vivisectionists battled with the medical community over the use of

animal subjects in experiments both critical and trivial, and lost. Since

then any objection to such experiments has been seen as sentimental,

childish, and unprogressive. My novel is my attempt to think about this

again. Also to ask what it means to be a human animal. I’ve got no easy

answers and I’m not trying to proselytize. I hope readers will also be

interested in thinking about these things.

The book was a great excuse to

look at some of the recent, incredible work being done on animal

cognition. Apparently the military toyed with the idea of using crows in

the hunt for Osama bin Laden, because of their superior facial recognition

skills. I watched you-tube videos of crows sledding and persuaded myself I

was doing research. Funny cat videos! Octopi escaping their tanks. Chimps

demonstrating their amazing abilities with short-term memory. Elephants

painting. Kathryn Hunter’s incredible performance as Red Peter in “Kafka’s

Monkey.”

The world is a complicated, surprising, often horrible and often beautiful

place. I just hope we can keep it. We’re not the only ones who live here.

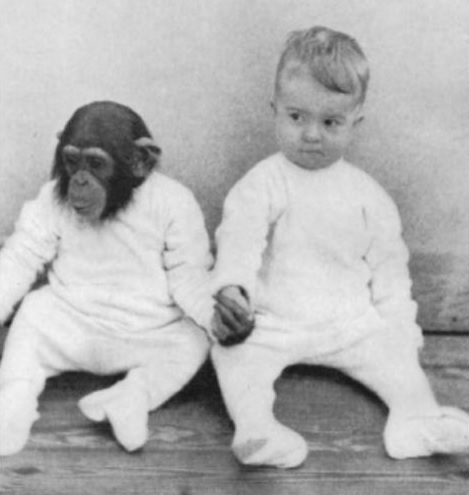

Kellogg, Gua and Donald

|

Kellogg's experimental subject was a seven-month-old chimpanzee called Gua, who had been forcibly removed from her family at the Anthropoid Experimental Station of Yale University, at Orange Park, Florida. In line with thinking of the time, the ideal environment for human education was the nuclear family. In June 1931, Kellogg set up home with his wife Luella, their ten-month-old son Donald and Gua. The only difference from any other family was that both infants faced a daily range of tests, including of their physiological state (blood pressure and weight, for example) and language comprehension, problem solving and obedience behaviour. It was an intensive programme, which consumed every moment of the Kelloggs' time and grew increasingly difficult as Gua matured. The results were fascinating. While not disputing that heredity played an important role in infant learning, the Kelloggs concluded that environment was also crucial: just as the 'African aboriginal who is raised in the United States becomes civilized as a result of his removal to the civilized environment', so too Gua adopted aspects of his 'civilized environment'. In some aspects, Gua became 'more humanized' than Donald: she was better able to skip, she was more cooperative and obedient, she was more skillful in opening doors and had a 'superior anticipation of the bladder and bowel reactions'. Most important, she was a faster learner. The main problem the Kelloggs faced was that Donald began to copy Gua. At fourteen months, Donald could be heard imitating Gua's food bark. Most worryingly, Donald was not acquiring human language. Although both Donald and Gua responded to vocal stimulus (increasingly, Donald surpassed Gua), 'neither subject really learned to talk during the interval of the research'. The experiment continued until March 1932, when Gua was returned to the primate colony in Orange Park. |

Sister and brother: Gua and Donald. This image was published in W. N. Kellogg and L. A. Kellogg, The Ape and the Child. From the first time they were introduced to each other, Donald and Gua were raised as though they were both human infants. In the words of the Kelloggs, Gua was made 'a thoroughly humanized member of the family of the experimenters, who would serve respectively in the capacities of adopted "father" and "mother".'  Gua |

—Joanna Bourke, What It Means to be Human: Reflections from 1791 to the Present (London: Little, Brown, 2011)

Writing

Foyles:

Before the success of The

Jane Austen Book Club, many of your fans would have described

you as a science fiction and fantasy writer. Do you think the

instinctive resistance of many readers to the genre is finally being

overcome?

Fowler: The real world, whatever

that means, is increasingly science fictional. In one day, I heard three

separate stories on the radio - one about OncoMouse™, the first patented

animal, one about a woman convicted of the murder of her fiancé based

solely on the evidence of her brain scan, and one about a computer program

that will, for a modest fee, pray for people ceaselessly. Realism is no

longer sufficiently realistic and even the most literary of writers have

begun to notice. The revolution takes place on Twitter. The sixth mass

extinction event is well underway. You can make your own gun on your own

3D printer. The Great Divide is no longer great. Or even a divide.

Foyles: One

of the most striking characteristics of the book is its deft blending

of emotional powerfully storytelling with sharp humour. Was this a

difficult balance to achieve?

Fowler: It was a necessary balance

to achieve. I'm trying to deal with some issues I personally find

important, but very painful and I wouldn't subject a reader, much less

myself, to that without the leaven of humor. The world is much more

terrible than I ever imagined when I was a child, but it is also much

funnier. I try to make do with that.

—"Questions and Answers," Foyles

The Title

Rehm:

Karen Joy Fowler and we're talking about

her new novel titled, "We Are All Completely Beside Ourselves." Talk

about that title.

Fowler: It's a phrase that my

mother used to use and that therefore I use fairly frequently and when I

use it, I mean that we are a little overexcited but I'm hoping that the

meaning of the novel begins to change as you, the meaning of the title

begins to change as you read the novel.

That I am talking about our situation in the world and our relations with

the other animals and the creatures that we share the world with and that

we have more in common, I hope. One of the messages of the novel is

hopefully that we have so much in common with the creatures that we share

the world that we...

—"Karen Joy Fowler: We Are All Completely Beside Ourselves," The Diane Rehm Show (2013)

|

Comprehension

Check |

|

Study Questions |

Review Sheet

Characters

Rosemary Cooke, Rosie, Rose – "a great talker as a child" (1); "In 1996, I was twenty-two years old, meandering through my fifth year at the University of California, Davis" (5–6); "I threw that glass down as hard as I could" (10); "I'm Rosemary Cooke" (11); "I'm a pretty good climber, for a girl" (13); "'Rosie had such good SATs...aced them. Especially the verbal'" (23); "had boundary issues [as a kindergartener]" (30); "walked out the door [of Cooke grandparents' house] and I intended to walk the whole way home" (39); "sent back home the next day, because, [Cooke grandparents] said, I'd turned out to be a handful and real noisy to boot" (40); "As a child, I chose to escape unhappy situations by sleeping through them" (52–53); "I spent the first eighteen years of my life defined by this one fact, that I was raised with a chimpanzee" (77); "my elbow hurt and then it turned out to be broken" (82); Christmas in Waikiki "was my first time on an airplane" (86); "I hope you haven't assumed that just because I had no friends I'd had no sex" (148); "For the last seven years, I've been a kindergarten teacher" (293)

Lowell

Cooke – "The fact that my brother's name was

not Travers was the most persuasive detail in Ezra's account" (45);

"when we were kids, my brother was my favorite person in the whole

world" (45); "a good poker player" (45); "the FBI had told us that my

brother had been in Davis in the spring of ’87, about a year after he

took off" (46); "The last time I saw him, I was eleven years old and he

hated my guts" (47); "refused to set foot in the new house" (54);

"Lowell is my brother's real name. Our parents met at the Lowell

Observatory in Arizona at a high school summer science camp" (55); "home

at last, climbing the stairs in the dark without anyone hearing him and

coming into my room, waking me up. 'If only,' he said—eleven years old

to my five, socking me high on the arm so the bruise would be hidden by

my T-shirt sleeve—'if only you had just, for once, kept your goddamn

mouth shut.' I have never in my life, before or after, been so happy to

see someone" (64); "had Luke Skywalker's haircut, but the color was pure

Han Solo" (66); "started seeing a counselor" (67); "accepted to Brown

University" (141); "He's worked for decades as a spy in the factory

farms, the cosmetic and pharmaceutical labs" (306)

Fern – Rosemary "followed Fern's lead in most

things" (62); "I tell you Fern is a chimp and, already, you aren't

thinking of her as my sister" (77); "Lowell's little sister, his shadow,

his faithful sidekick" (78); "She was my twin, my fun-house mirror, my

whirlwind other half" (78–79); "My very earliest memory, more tactile

than visual, is of lying against Fern. I feel her fur on my cheek. She’s

had a bubble bath and smells of strawberry soap and wet towels. [...] I

see her hand, her black nails, her fingers curling and uncurling. […]

She is giving me a large golden raisin" (80); "The things I can do that

Fern can't are a molehill compared to the mountain of things she can do

that I can't" (82); "Fern particularly loved Charlotte's

Web, probably because she'd heard her own name so often when

Mom read it. Was that where Mom had gotten the name? [...] And what had

she meant by it then, naming our Fern after the only human in the book

who can talk with nonhumans?" (174)

Dr. Vince Cooke – "college professor and a pedant to the

bone. Every exchange contained a lesson" (6); "This [fly-fishing] was

the meditative activity he favored" (18); "diagnosed with diabetes a few

years back...become a secret drinker" (18); "a chain-smoking,

hard-drinking, fly-fishing atheist from Indianapolis" (20); "You all

blame me, Dad said. My own goddamn children, my own goddamn wife. What

choice did we have? I’m as upset as anyone" (64); "The man who saw the

stars in my mother's eyes died in 1998. [...] he had a heart attack that

he mistook for the flu" (278)

Mrs.

Cooke – "an infamous bridge hustler" (14); "my

mother wasn't having a baby; she was having a nervous breakdown" (40);

"'I'd [Vince Cooke] come to see the heavens...But the stars were in her

eyes'" (55); "vaporous; she emerged from her bedroom only at night and

always in her nightgown [...] She would start to speak, her hands

lifting, and then be suddenly silenced by the sight of that motion, her

own hands in the air. She hardly ate and did no cooking" (60); "'Conga

line,' Mom calls. She snakes us through the downstairs, Fern and I

dancing, dancing, dancing behind her" (95)

Harlow

Fielding – "Long, dark hair...stood and cleared

the table with one motion of her arm...beautiful biceps" (7); "Big white

teeth" (10); "I'm Harlow Fielding. Drama department" (11); "She slid her

arms under her butt and then under her legs so her cuffed wrists ended

up twisted in front of her [...] 'I have very long arms'" (12);

"Everyone seemed to know Harlow [at the Paragon bar]" (36); from Fresno,

in Davis three years" (36); "I [Rosemary] was okay with her acting-out

because I'd seen it before. [...] When the revelation finally came, it

complicated my feelings toward Harlow more than it illuminated them"

(137); "I [Rosemary] felt comfortable with her in a way I never felt

comfortable with anyone" (138); "Harlow's different idea was to pick the

lock on the suitcase we did have, open it, and see what was inside"

(142)

Reg

– Harlow's boyfriend (14); "big guy,

with a thin face...nose like a knife" (8); "'Reg kicked

me [Harlow] out'" (31); "had a sharp nose that swerved slightly left.

Surfer-type, but in a minor key. He was a good-looking guy" (41)

Ezra

Metzger – Rosemary's apartment manager (31);

"applied for a job in the CIA" (32); "had a habit of sucking on his

teeth so his mustache furled and unfurled" (32); "didn't think of

himself as the manger of the apartment house so much as its beating

heart" (32); "saw conspiracies" (32); "Ezra pled guilty,

got eight months in a minimum-security prison in Vallejo" (271); "Ezra's

mustache was gone" (271)

Todd

Donnelly – Rosemary's roommate at UC Davis (30);

"had a third-generation Irish-American father and a second-generation

Japanese-American mother, who hated each other" (33); "Ever since the

Great Eejit Incident, Todd had reached into his Japanese heritage when

he needed an insult" (33); "his girlfriend, Kimmy Uchida" (34); "a

junior majoring in art history...a nice, quiet guy...his Irish father,

from whom he got his freckles, and his Japanese mother, from whom he

got his hair" (134)

Todd's

mother – "I've been talking with Todd's mother

recently and I think she'll agree to represent Lowell" (306)

Dr. Sosa – "The name of the class was Religion and

Violence. The professor, Dr. Sosa, was a man in his middle years with a

receding hairline and an expanding belly. He was a popular teacher, who

sported Star Trek ties and

mismatched socks, but all ironically" (146–47); "Dr. Sosa and I had a

silent rapport" (147); "Chimpanzees, he said, shared our

propensity for insider/outsider violence" (147); "said that among

chimpanzees, the lowest-status male was higher than the highest-status

female" (148)

Madame

Defarge – "a ventriloquist’s dummy—antique, by

the look of it. […] 'Madame Defarge,' […] 'Madame Guillotine'" (144)

Officer Arnie Haddick – "hair was receding from his forehead

in a clean, round curve that left his features nicely uncluttered,

like a happy face" (12)

Grandma

Donna – "my mother's mother" (18);

"we all ate more at Grandma Donna's...where the piecrusts were flaky and

the orange-cranberry muffins light as clouds; where there were silver

candles in silver candlesticks, a centerpiece of autumn leaves, and

everything was done with unassailable taste" (19); "loved her children so

much there was really no room for anyone else" (21); "began coming over

every day to watch me [Rosemary]" (60); "a great reader of historical

biographies" (63); "drove once to Marco's, intending to force Lowell home,

but she came back defeated, face like a prune" (63)

Grandma

Fredericka – "my father's [mother]" (18); "At

Grandma Fredericka's, the food had a moist carbohydrate heft...Her

house was strewn with chap Asian tchotchkes" (19); "believed that

bullying guests into second and third helpings was only being polite"

(19); Rosemary "shipped off to my Grandpa Joe and Grandma

Fredericka's" (37); "the quilt over me was my quilt—hand-sewn by

Grandma Fredericka back when she'd loved me, appliquéd with sunflowers

that stretched from the foot to the pillow" (53)

Kitch, Katherine

Chalmers – "[Lowell] had an on-again, off-again

relationship with a girl. Her name was Katherine Chalmers, but

everyone called her Kitch. Kitch was Mormon" (114); "'You'd [Rosemary]

probably be a great teacher'" (123); "walking together to his

[Lowell's] basketball practice [...] when they ran into Matt...my

favorite grad student" (124)

Peter

– "My cousin Peter's tragic SAT scores"

(22); "could make a white sauce when he was six years old" (22); "all-city

cellist...voted Best-Looking at his high school. He had brown hair and the

shadows of freckles dusted like snow over his cheekbones, and old scar

curving across the bridge of his nose and ending way too close to his eye"

(22); "Everyone loved Peter" (22); "drove [Janice] to school every morning

and picked her up every afternoon that he didn't have orchestra" (22)

Uncle Bob – Rosemary's mother's brother (18);

"sees the whole world in a fun-house mirror" (21)

Aunt Vivi – cousin Peter's mother (22); "has mysterious flutters, weeps, and frets" (22)

Janice

– Peter's sister (22); "In 1996, Janice

was fourteen, sullen, peppered with zits, and no weirder than anyone

else (which is to say, weird on stilts)" (22)

Will Barker – "estate lawyer" (20); "thought my

mother hung the moon" (20)

Mary – "I made up a friend for myself. I

gave her the half of my name I wasn't using, the Mary part, and

various bits of my personality I also didn't immediately need. We

spent a lot of time together, Mary and I, until the day I went off to

school" (25); "There's something you don't know yet

about Mary. The imaginary friend of my childhood was not a little girl.

She was a little chimpanzee. So, of course, was my sister Fern" (77);

Rosemary invents "Mary, to even the score. Mary could do everything Fern

could and then some. And she

used her powers for good instead of evil, which is to say only under my

direction and on my behalf [...] The best thing about Mary was that she

was kind of a pill" (83)

Grandpa Joe – "my father's father, painted it

[Rosemary's saltbox house bedroom] blue" (26)

Melissa – "For me [Rosemary], he [Dr. Cooke]

engaged a babysitter, Melissa, a college student with owlish glasses

and blue streaks zigzagging, like lightning, through her hair" (68);

"would teach me a new word from the dictionary" (69); "now an

established part of the household" (69)

Russell

Tupman – "the big boy from the high

school...lighting a weary cigarette and sucking it in...I was charmed.

I was flattered. I fell instantly in love" (70–71); sixteen (71);

"the cops busted Russell. Grandma Donna told me that he'd thrown a

Halloween party at the farmhouse" (85)

Tamara

Press – "when our dog Tamara Press had died,

our mother had been devastated" (77)

Setting

Place

Time

Sample Student Responses to Karen Joy Fowler's We Are Completely Beside Ourselves

Response 1:

|

|

Reference

Fowler, Karen Joy. We Are Completely Beside Ourselves. 2013. London: Serpent's Tail, 2014. Print.

| Links |

Story, Reviews

The

Kellogg Experiment

|

| Media |

|

|

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

| Karen Joy Fowler |

|

Home | Reading and Analysis for the Study of English Literature | Literary Terms

Last

updated

November 27, 2015