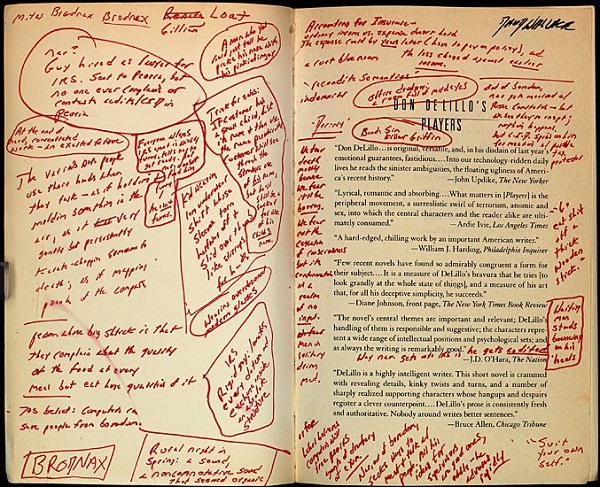

Jean-Honoré Fragonard, The Swing, 1767, oil on canvas, The Wallace Collection

- The origin of Fragonard's The

Swing is by chance known. The writer Charles Collé

recorded having met the painter Gabriel-François Doyen on 2

October 1767: 'Would you believe it!' A gentleman of the court

had sent for him shortly after a religious painting of his had

been exhibited in Paris and when Doyen presented himself he

found him at his 'pleasure house' with his mistress. 'He

started by flattering me with courtesies', Doyen related, 'and

finished by avowing that he was dying with a desire to have me

make a picture, the idea of which he was going to outline. "I

should like, Madame (pointing to his mistress) on a swing that

a bishop would set going. You will place me in such a way that

I would be able to see the legs of the lovely girl, and better

still, if you want enliven your picture a little more..." I

confess, M. Doyen said to me, that this proposition, which I

wouldn't have expected, considering the character of the

picture that led to it, perplexed me and left me speechless

for a moment. I collected myself, however, enough to say to

him almost at once: "Ah Monsieur, it is necessary to add to

the essential idea of your picture by making Madame's shoes

fly into the air and having some cupids catch them."' Doyen

did not accept the commission, however, and passed it on to

Fragonard. The identity of the patron is unknown, though he

was at one time thought to have been the Baron de

Saint-Julien, the Receiver General of the French Clergy, which

would have explained the request to include a bishop pushing a

the swing. This idea as well as that of having himself and his

mistress portrayed was evidently dropped by the patron,

whoever he may have been. The picture was depersonalized and,

due to Fragonard's extremely sensuous imagination, became a

universal image of joyous, carefree sexuality.

The theme is that of love and the rising tide of passion, as intimated by the sculptural group in the lower centre of the picture. (Dolphins driven by cupids drawing the water-chariot of Venus symbolize the impatient surge of love). Beneath the girl on the swing, lying in a great bush, a tangle of flowers and foliage, is the young lover, gasping with anticipation. The bush is, evidently, a private place as it is enclosed by little fences. But the youth has found his way to it. Thrilling to the sight now offered him, the youth reaches out with hat in hand. (A hat in eighteenth-century erotic imagery covered not only the head but also another part of the male body when inadvertently exposed.) The feminine counterpart to the hat was the shoe and in The Swing the girl's shoe flies off her pretty foot to be lost in the undergrowth. This idea had been suggested originally by Doyen, as he recounted to Collé, and in French paintings of the period a naked foot and lost shoe often accompany the more familiar broken pitcher as a symbol of lost virginity.

However, all these erotic symbols would lie inert on the canvas had not Fragonard charged the whole painting with the amorous ebullience and joy of an impetuous surrender to love. In a shimmer of leaves and rose petals, lit up by a sparkling beam of sunshine, the girl, in a frothy dress of cream and juicy pink, rides the swing with happy, thoughtless abandon. Her legs parted, her skirts open; the youth in the rose-bush, hat off, arm erect, lunges towards her. Suddenly, as she reaches the peak of her ride, her shoe flies off. (Hugh Honour and John Fleming 628–29) - A woman on a swing was an established motif in French Rococo art, especially in paintings of fêtes galantes, those poetic celebrations of the aristocratic life of leisure. Children were occasionally shown enjoying the pastime, very infrequently men. Women and girls monopolized it and the swing soon acquired further connotations. It seemed to epitomize the pleasure-loving, licentious spirit of the ancien régime and in particular the fickleness and inconstancy ascribed to women, especially in high society, their teasing changes of mind if not of heart in the perpetual to-and-fro game of light-hearted, feet-off-the-ground flirtation. (Hugh Honour and John Fleming 614)