Faculty of Arts,

Chulalongkorn University

Trifles

(1916)

Susan

Glaspell

(July 1, 1876 – July 27, 1948)

Notes

The

one-act play Trifles was first

performed by Glaspell's theater group, the Provincetown Players, in 1916

with Glaspell playing Mrs. Hale and her husband, George Cram Cook, playing

Mr. Hale.

36

party telephone: a shared

telephone service in the early days of telephone from late nineteenth

century to mid-twentieth century, usually in rural areas or for non

businesses, where several subscribers are connected to the same telephone

line strung out miles between many residences

- By the mid-1930s, telephone service was a staple for the folks in

rural Nebraska. But, unless you were a business, they were all party

lines. This meant that there would be as many as 10 and sometimes 20

subscribers on one line. ("Remembering

Party Telephone Lines")

- "Out home," said the girl from Texas, "I live on a ranch. It's miles

from a railroad and the only thing that keeps us in touch with

civilization is a telephone. It is a single wire run out from the

nearest town, and exactly seventeen families are on the line. So when

you ring up if you listen you will hear just sixteen receivers taken off

the hook all along the line. [...]" ("The

Party Telephone")

36

he put me off:

- put off (Merriam-Webster)

transitive verb

1 a: disconcert b:

repel

2 a: to hold back to a later

time b: to induce to wait

<put the bill collector off>

3: to rid oneself of: take off

4: to sell or pass fraudulently

Examples of PUT OFF

<never put off until

tomorrow what you can do today>

<put off your coat and stay

awhile>

- put someone off (Oxford

Dictionaries)

1 Cancel or postpone an

appointment with someone:

he’d put off Martin until

nine o’clock

2 Cause someone to lose

interest or enthusiasm:

she wanted to be a nurse, but the thought of night shifts put

her off

2.1 Cause someone to feel

dislike or distrust:

she had a coldness that just put me

off

3 Distract someone:

don’t put me off—I’m

trying to concentrate

- put off (Macmillan

Dictionary)

phrasal verb, transitive

1 to make someone not want to

do something, or to make someone not like someone or something

Lack of parking space was putting potential

customers off.

Robert’s attitude towards women really puts

me off.

- put someone off someone/something: I put

him off the idea of

going shopping with me.

- put someone off doing something: All this rain really puts

you off going out

after work.

2 to delay doing something,

especially because you do not want to do it

I was trying to put off the

moment when I would have to leave.

You can’t put the decision off any longer.

- put off doing something: He was glad to have an excuse to put

off telling her the news.

3 to change the time or date of

something so that it happens later than originally planned, especially

because of a problem

They had to put the wedding off because the bride’s mother had

an accident.

- put off doing something: I’ll put

off going to Scotland until you’re well enough to look after

yourself again.

4 to tell someone that you

cannot see them or do something until a later time

We’ll have to put George off if your mother’s coming on

Thursday.

5 to prevent someone from

concentrating on something so that they have difficulty doing it

Stop laughing – you’ll put her

off.

a. put someone off their

stride/stroke to stop someone from thinking clearly

He was determined not to be put off his

stroke by her presence.

6 to switch off a machine or

piece of equipment

Please put off the television

and do your homework.

7 to stop a car, bus etc and let someone get out of it

I’ll put you off

by the bus stop.

37

done up: exhausted; worn out;

tired out

37

to set down: to sit down

37

sound:

- sound (Merriam-Webster)

4 a: thorough b:

deep and undisturbed <a sound sleep>

c: hard, severe <a sound

whipping>

38

Well, can you beat the women!:

Can you believe the women!; Women are impossible creatures!; It's hard to

understand women

38

gallantry:

- gallantry (Merriam-Webster)

2 a: an act of marked

courtesy b: courteous

attention to a lady c:

amorous attention or pursuit

38

roller towels:

|

- A long towel with the ends joined and hung on a roller or one

fed through a device from one roller holding the clean part to

another holding the used part. (Oxford

Dictionaries)

- A towel with the two ends sewn together, forming a loop, which

is hung on a roller. (Cowboy

Bob's Dictionary)

|

40

close:

- close (adj.) (Merriam

Webster)

1: having no openings: closed

2 a: confined or carefully

guarded <close arrest> b (1) of

a vowel: high

13 (2): formed with the

tongue in a higher position than for the other vowel of a pair

3: restricted to a

privileged class

4 a: secluded, secret b: secretive <she could tell us

something if she would … but she was as close

as wax — A. Conan Doyle>

5: strict, rigorous <keep close watch>

6: hot and stuffy <a room

with an uncomfortably close atmosphere>

7: not generous in giving or

spending: tight

8: having little space between

items or units <a close weave>

<a close grain>

9 a: fitting tightly or exactly

<a close fit> b: very short or near to the

surface <a close haircut>

10: being near in time, space,

effect, or degree <at close range>

<close to my birthday>

<close to the speed of

sound>

11: intimate, familiar <close friends>

12 a: very precise and attentive

to details <a close reading>

<a close study> b: marked by fidelity to an original

<a close copy of an old

master> c: terse,

compact

13: decided or won by a narrow

margin <a close baseball

game>

14: difficult to obtain

<money is close>

15 of

punctuation: characterized by liberal use especially of

commas

41

tippet:

41 quilt:

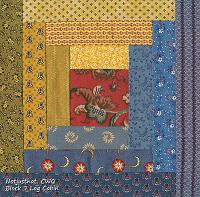

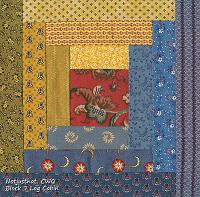

41 log cabin pattern: a

classic and popular quilt pattern

Log cabin pattern block

Detail of quilt in log cabin pattern, courthouse steps variation,

c. 1860 |

- Pieced Quilts: Log

Cabin, Illinois State Museum Society

The Log Cabin block consists of light

and dark fabric strips that represent the walls of a log

cabin. A center patch, often of red cloth, represents the

hearth or fire.

Quilt historians found that the Log

Cabin design became popular in 1863, when the Union army was

raising money for the Civil War by raffling quilts. President

Abraham Lincoln grew up in a log cabin. The pattern may have

been a symbol of loyalty to him as head of the Union.

- Jane Hall, "Log

Cabin Quilts: Inspirations from the Past"

When I began quilting, I was told

with great authority that Log Cabin quilts were always tied,

never quilted. Once I began to collect old quilts, I

understood why. These foundations were often waste fabrics of

different weights, perhaps recycled, and in the days before

sewing machines were widely available, would be almost

impossible to quilt through by hand.

- Patricia Cox and Maggi McCormick Gordon, Log Cabin Quilts Unlimited:

The Ultimate Creative Guide to the Most Popular and

Versatile Pattern (Chanhassen, MN: Creative

Publishing, 2004)

However it traveled, by the 1860s the

pattern had become one of the most popular in the United

States. The block's structure, based on narrow strips and

small squares, was ideal for use by quiltmakers on the

American frontier who had little access to new fabric and so

became masters of recycling.

The Quilting

Because Log Cabin quilts have so many

seams, few quilters attempt to sew the layers together with

intricate quilting designs. Not only would the effect be lost

in the mass of seams and patterns, but also hand stitching

would be very laborious. Many historical examples are tied

with yarn, thread, or string to secure the layers.

- Blocks in the "Quilt Code": Log

Cabin

Stroud, on the other hand, says the block is "a sign that

someone needed assistance."

- Log

Cabin Quilts—A Short History, Quilt

Views, American Quilter's Society

Early Log Cabin blocks were

hand-pieced using strips of fabrics around a central square.

In traditional Log Cabin blocks, one half is made of dark

fabrics and the other half light. A red center symbolized the

hearth of home, and a yellow center represented a welcoming

light in the window. Anecdotal evidence, based on oral

folklore, suggests that during the Civil War, a Log Cabin

quilt with a black center hanging on a clothesline was meant

to signal a stop for the Underground Railroad.

|

42 hard:

- hard (Merriam-Webster)

8

a (1): difficult to bear or

endure <hard luck> <hard times> (2):

oppressive, inequitable <sales taxes are hard

on the poor> <a hard restriction>

b (1): lacking consideration,

compassion, or gentleness: callous <a hard

greedy landlord> (2):

incorrigible, tough <a hard gang>

c (1): harsh, severe, or

offensive in tendency or effect <said some hard

things> (2):

resentful <hard feelings>

(3): strict, unrelenting

<drives a hard bargain>

d: inclement <hard

winter>

e (1): intense in force, manner,

or degree <hard blows> (2): demanding the exertion of

energy: calling for stamina and endurance <hard

work> (3):

performing or carrying on with great energy, intensity, or persistence

<a hard worker>

f: most unyielding or

thoroughgoing <the hard political

right>

Biography

But run-of-the mill reporting did not satisfy Glaspell

for long; she idealistically conceived of herself as a reformer whose

mission was to show humanity the way to greater achievement through her

writing. She persuaded the editors to entrust her with a column on current

affairs, in which she reclaimed the detached wry tone she had developed for

the Weekly Outlook, fabricating a

highly critical "News Girl." From this van-[end of page 26] tage point, she

plied her readers with ironic commentary and advice, taking her cue from

local events or her reading. When several articles that appeared in the Ladies Home Journal particularly

incensed her, she devoted an entire column to attacking the author's

outdated convictions. The Ladies Home

Journal—which in later years would publish some of Glaspell's

stories—had first appeared in 1883 and by the end of the century had become

the most widely read and influential women's magazine. Traditional in many

respects, it had no truck with the growing suffrage movement, but its pages

rejected the frail, ethereal lady, promot-[end of page 27] ing instead the

self-disciplined, hardworking woman who knew how to run her home. Glaspell

objected to the articles in question because they accused the young

college-educated American woman of "buy[ing] indecent books and haunt[ing]

the theater for indecent plays." Her "News Girl" assured readers that Des

Moines college girls, far from acquiring immoral habits, had "learned how to

think and formed a desire to be of use in the world." [...]

The most dramatic case Glaspell covered for the Des

Moines Daily News was the Hossack murder, which impressed her so

greatly that, sixteen years later, she used it as the basis for Trifles,

the play that made her name. Glaspell first reported on the case on 3

December 1900 and covered it until the jury's decision was announced on 10

April 1901. Her initially hostile, fully orthodox attitude toward Mrs.

Hossack, accused of bludgeoning her husband with an axe as he slept, became

more sympathetic after she visited the Hossack home. There, taking in

trifling clues that together formed a picture of Mrs. Hossack's life,

Glaspell talked to members of the family and neighbors. In spite of the

varied experiences that she had gained in over a year of reporting, she was

horrified to learn that Mr. Hossack had beaten his wife regularly. This

revelation of the grimier side of the institution of marriage opened her

eyes to the fact that women can be trapped with no hope whatever of escape

or help from society; possibly, she even found herself understanding her

mother's position more clearly. Too late, Glaspell tried to sway public

opinion with sympathetic reporting and headlines such as "Mrs. Hossack May

Yet Be Proven Innocent." But in spite of her efforts, Mrs. Hossack was found

guilty and sentenced to life imprisonment with hard labor; two years alter,

however, unconvinced by the evidence, a second jury ordered her release.

This case lay heavily on Glaspell's mind; she may have tried unsuccessfully

to mold it into a magazine story. It was not until 1916, when she was more

experienced with the wrongs inflicted on women, that she found the

appropriate angel. In Trifles (1916)—and

the short story "A Jury of Her Peers" (1917)—Glaspell transformed the case,

giving the women who had been silenced at the trial voices of their own; she

focused on the [end of page 28] motive of the crime—totally incomprehensible

to a jury of men—and thus attempted to clear Mrs. Hossack's name and make

amends for her tardy understanding and her inability to help at the time.

Weary of newspaper work, and humbled by the Hossack case,

Glaspell returned to Davenport.

[...] few specific details remain in Glaspell's revisioning of the Hossack

case. [...] Of the names of the participants, only Henderson is used,

assigned to the county attorney rather than the defense lawyer. Margaret

Hossack has been renamed Minnie Foster Wright, the pun on the surname

marking her lack of "rights," and implying her "right" to free herself

against [end of page 153] the societally sanctioned "right" of her husband

to control the family, a right implicit in the Hossack case.

Glaspell's most striking alterations are her

excision of Minnie and the change of venue. The accused woman has been taken

away to jail before Trifles begins,

her place signified by the empty rocking chair that remains in her kitchen.

By not bringing Minnie physically on to the stage, the playwright focuses on

issues that move beyond the guilt or innocence of one person. Since the

audience never actually sees Minnie, it is not swayed by her person, but by

her condition, a condition shared by other women who can be imagined in the

empty subject position. And by situating her play in the kitchen, not at the

court, in the private space where Minnie lived rather than the public space

where she will be tried, Glaspell offers the audience a composite picture of

the life of Minnie Wright, Margaret Hossack, and the countless women whose

experiences were not represented in court because their lives were not

deemed relevant to the adjudication of their cases. Most important, by

shifting venue, Glaspell brings the central questions never asked in the

original Hossack case into focus: the motives for murder, what goes on in

the home, and why women kill.

Motives are writ large in Trifles.

The mise-en-scène suggests the harshness of Minnie's life. The house is

isolated, "down in a hollow and you don't see the road" (21)—dark,

foreboding, a rural, gothic scene. The interior of the kitchen replicates

this barrenness and the commensurate disjunctions in the family, as the

woman experienced them. Things are broken, cold, imprisoning;p they are also

violent. "Preserves" explode from lack of heat, a punning reminder of the

casual relationship between isolation and violence. The mutilated cage and

bird signify Wright's brutal nature and the physical abuse his wife has

borne.

[...]

[...] [page 158] By having the women assume the central positions and

conduct the investigation and the trial, she actualizes an empowerment that

suggests that there are options short of murder that can be imagined for

women. Mrs. Peters and Mrs. Hale may seem to conduct their trial sub rosa,

because they do not actively confront the men: but in Mrs. Hale's final

words, "We call it—knot it, Mr. Henderson" (30), ostensibly referring to a

form of quilting but clearly addressed to the actions the women have taken,

they become both actors and namers. Even if the men do not understand the

pun—either through ignorance or, as Judith Fetterley suggests, through

self-preservation—the audience certainly does.

[page 53] The sardonic humor of Minnie's

having married "Mr. (W)right" (Gubar and Hedin 788) cannot mask the harsh

reality of his treatement of her. Playing further with these homonyms,

Veronica Makowsy observes, "Minnie...now 'writes' the script for her life

according to what [John] considers 'right.'" ("Susan Glaspell" 52). As Joan

Radner and Susan Lanswer explain, Minnie has no means of directly conveying

her plight, which results in her creation of a range of semiotic codes the

other women must dicipher:

|

By coding, then we mean the adoption of a system of signals...that

protect[s] the creator from the dangerous consequences of directly

stating particular messages....Minnie Wright did not deliberately

encode her murderous rage and despair into the chaos of her kitchen

and sewing basket, but she nonetheless left a message. (414–15) |

And Mrs. Hale's and Mrs. Peters's reading of that message—what Minnie Wright

crafted—is, in Glaspell's schema, an echoed response of

righting/writing/writing.

One of the ironies of Trifles/"Jury"

is that, had Minnnie enjoyed the friendship of other women, she might not

have generated these signs. Another, of course, is that the misanthropy of

her husband compelled ehr to avoid such companionship. Her isolation, in

fact, creates the context for the reading of her codes, particularly the

quilt. Analogously, Glaspell's actual writing, like [end of page 53]

Minnie's quilting, is a solitary process. Yet the ability to understand such

creativity, or even to generate it successfully, Glaspell suggests, mandates

collaboration. As alkalay-Gut has noted, the distinction between quilting

and knotting has great

significance for the plot. Toward the middle of the play Mrs. Hale mentions

that Minnie "didn't even belong to the Ladies Aid," as she "couldn't do her

part" (in terms of making financial contributions) and felt "shabby" and

therefore was incapable of enjoying the women's group (14). This information

is strategic for the women's later discovery of Minnie's method of quilt

making. When they reveal that they "think she was going to—knot it" (24),

they are not only referring to their conclusion that Minnie indeed tied the

knot that strangled her husband but also to their understanding of her

isolation:

|

Patchworking is conceived as a collective activity, for although

it is the individual woman who determines the pattern, collects,

cuts the scraps, and pieces them together, quilting work on an

entire blanket is too arduous for one person. Minnie's patchwork

would have been knotted and not quilted because knotting is easier

and can be worked alone. (Alkalay-Gut 8) |

Another ironic element of the quilting image is its

connotations for the Wright home. Physical as well as spiritual cold

permeates the play; Mrs. Hale's memory of John Wright prompts a "shiver" as

she describes him: "Like a raw wind that gets to the bone" (22). Cold and

hard, Wright seems unlikely to have been affected by the warmth of Minnie's

quilting efforts. Playing on Minnie's maiden name, Foster, Veronica Makowsky

points to Glaspell's development of Minnie's frustrated efforts at

"nurturing domesticity" ("Susan Glaspell" 52). The women perceive the

loneliness behind Minnie's use of the scraps of cloth, initially intended

for the quilt, as coverings for the last bit of warmth in her life, her

strangled canary.

In the story's closing scene, Mrs. Hale and Mrs.

Peters silently communicate to each other their mutual decision to conceal

the body of the songbird. Mrs. Peters is the first to move, but she is

unable to fit the box holding the bird into her handbag. Mrs. Hale takes it

from her, hiding it in her large coat pocket just as the men enter the room.

The last words of the story are Mrs. Hale's. In response to a question asked

"facetiously" by the county attorney as to how Mrs. Wright planned to finish

her quilt, Mrs. Hale replies, "We call it—knot it." In that final statement,

Susan Glaspell not only calls up the image of Minnie having tied the rope

around her husband's neck, but she also reenforces the other two women

bonding (or "knotting") together, silently refusing to recognize (saying

"not" to) the authority of the men.

Study Guide for Susan Glaspell's Trifles

Topics to think

about:

|

Study Questions

- Silences:

- What

moments in the play happen in silence? Why is this

important?

- Laughter: Who

laughs? At whom? When? When is laughter mentioned? What

does laughter mean in each instance?

- Loyalty:

- Communication

- In

what ways do characters communicate with each other?

How do messages get across from one party to another?

- Do

women communicate differently from men? How do the

women communicate without sound?

- Do

the two women communicate differently from each other?

- Look

up the word close (30)

in a collegiate or large unabridged dictionary like Merriam Webster

or Random House.

Which meaning is used in this description of John

Wright? Even without the dictionary's help, can you

make an accurate guess from the context of Mrs. Hale's

lines regarding Minnie Wright and from the story—from

what we know of John Wright's character—what close

means here? How does John Wright's being

close affect Minnie Wright's shying away from society

and losing touch with friends and acquaintances?

- What

solutions does Trifles

suggest to communication problems?

- Irony: What ironies

do you find in the play?

- Dialog

- Notice

how dialog is interrupted or becomes choppy at

different points in the play. What words are choked

off or able to come out? What actions are checked or

completed? What ideas are withheld or expressed, and

when? Who or what interrupts these dialogs or actions?

- Despite

so much that is interrupted or incomplete in Trifles

(ex. unwashed hand towels, bread dropped

beside its box, spoken sentences left unfinished), how

is discovery or disclosure achieved? How do we know

what someone is going to say even if that person does

not finish the sentence?

- Notice

how many lines the women have in the dialog when the

men are with them. How differently does Mrs. Peters

speak to the men when in their company compared to how

Mrs. Hale speaks to them? Does the way Mrs. Peters

speak change by the end of the play?

- Setting

- What

is the significance of the setting and the set?

- What

actions take place where? How are different characters

allotted space on the stage? How do the characters

associate themselves with particular spaces in the

setting and with each other throughout the play?

- What

is the significance of the rocking chair?

- Symbolism:

- quilt

- canary

- Look

in a dictionary of slang or idioms like The

American Heritage Dictionary of Idioms for

the meaning of these phrases.

- sing

like a canary (43)

- canary

in a coal mine (43)

- the

bird has flown (43)

- the

cat that ate/swallowed/got the canary (43)

- cage

- rocking

chair

- names

- Wright

- Minnie

- Foster

- Hale

- Character:

- How

does the ending of the play reveal character through

discovery? What information do you discover about the

characters? How is that information given?

- Examine

how the play characterizes characters who are not

there. Pick an absent character and consider the

techniques used to present them to us and how that

presentation affects our understanding of other

characters who are present, and of the story.

- Conflict: Explore

conflict in the play. Choose a conflict that intrigues

you and consider who is involved in it, and in what way.

How is the conflict resolved, or doesn't it?

- Crimes:

- Why

does Mrs. Hale feel guilty? What crimes has she done?

- What

does John Wright do that Mrs. Hale feels is criminal?

- What

are the limitations on the kinds of crimes that the US

judicial system of the time is equipped to handle?

- Justice:

|

Review Sheet

Characters

Martha Hale,

Mrs. Hale

– "larger and would ordinarily be called more comfortable looking"

(36)

Mrs. Peters – "a slight wiry

woman, a thin nervous face" (36)

Minnie Foster,

Mrs. John Wright – "'and there in that rocker...sat Mrs. Wright'"

(37); "'She was rockin' back and forth. She had her apron in her hand and

was kind of—pleating it'" (37); "'she looked queer...as if she didn't know

what she was going to do next'" (37); "'She just nodded her head, not

getting a bit excited'" (37); "'She just pointed upstairs'" (37); "'I sleep

sound'" (37); "'I [Mr. Hale] said I had come in to see if John wanted to put

in a telephone, and at that she started to laugh, and then she stopped and

looked at me—scared. (the COUNTY

ATTORNEY, who has had his notebook out,

makes a note) I dunno, maybe it wasn't scared. I wouldn't like to

say it was'" (38); "kept so much to herself. She didn't even belong to the

Ladies Aid. [...] She used to wear pretty clothes and be lively, when she

was Minnie Foster, one of the town girls singing in the choir. [...] that

was thirty years ago" (40); "'she was kind of like a bird herself—real sweet

and pretty, but kind of timid and—fluttery. How—she—did—change'" (42–43)

Henry

Peters, Sheriff Peters – "the Sheriff and

Hale are men in middle life" (36)

John

Wright

– a farmer neighbor of the Hales; "'I [Mr. Hale] spoke to Wright

about it [a shared telephone line] once before and he put me off, saying

folks talked too much anyway, and all he asked was peace and quiet—I guess

you know about how much he talked himself'" (36); "'I [Mr. Hale] didn't

know as what his wife wanted made much difference to John'" (36); "'He

died of a rope round his neck'" (37); "'he didn't drink, and kept his word

as well as most...and paid his debts. But he was a hard man.... Just to

pass the time of day with him—(shivers)

Like a raw wind that gets to the bone'" (42)

George

Henderson, young Henderson, County

Attorney, the lawyer – "the County

Attorney is a young man" (36); "'Come up to the fire, ladies'" (36);

"'Here's a nice mess [broken preserve jars]'" (38); "(with the gallantry

of a young politician) And yet, for all their worries, what would we do

without the ladies?" (38); "'Dirty towels!'" (38); "'I shouldn't say she

[Mrs. Wright] had the homemaking instinct'" (39)

Lewis

Hale, Mr. Hale – a farmer neighbor

of the Wrights

Harry

Hale – "Mrs. Hale's

oldest boy"; "'Harry and I [Mr. Hale] had started to town with a load of

potatoes'" (36); "'He's [John Wright] dead all right, and we'd better not

touch anything'" (37)

Frank –

deputy sheriff (36, 39); "'send Frank out this morning to make a fire for

us'" (36); "'I told him not to touch anything except the stove—and you

know Frank'" (36)

Setting

Wright farmhouse – "now abandoned

farmhouse of John Wright" (36); "'I've [Mrs. Hale] never liked this place.

Maybe because it's down in a hollow and you don't see the road...it's a

lonesome place and always was'" (42)

kitchen – "a gloomy kitchen,

and left without having been put in order" (36)

– "'When it dropped below zero last night'" (36)

Sample Student Reading Responses to Susan Glaspell's Trifles

Study Question: What is

the significance of the setting and the set?

Response 1:

|

|

Teerapong Wanichtamrong

2202235 Reading and Analysis in the Study

of English Literature

Acharn Puckpan Tipayamontri

January 7, 2009

Reading Response

A

None Place

“Down in a hollow and you don’t see the road” (42),

Mrs. Wright’s kitchen is in a house that is

literally unseen by passersby. In this setting that

is generally invisible, a crime has been committed

which no one sees or hears save possibly the suspect

who pleads ignorance and is not present in the play.

The case that will be tried in court will have no

female jury because the time of the play is when

women cannot be such a part of the legal system, nor

can they vote or be a part of the political system.

The setting then, is a time and place where Mrs.

Wright’s case effectively cannot be seen or heard.

In

this non place, the set is a kitchen where,

according to the sheriff, “the law,” there is

“nothing here but kitchen things” (38). Wiped of

existence and legal potential, the set and setting

of Trifles

is Glaspell’s genius ironic construction. Out of

sight, out of mind, goes the saying. By bringing

this dismissible space to her audience, Glaspell

forces them to look at and think about a place that

otherwise has no position in consciousness. The

things that unfold in this nonexistent

place—unwitnessed crime, unknown motive, and unfound

evidence leading to an untenable case—ask the

audience to reconsider its dismissibility. Rather

than being negligible, this none place becomes a

privileged peek into the unknown. And once known,

the place, its hidden female inhabitant, and her

secret conspirators, are not easy to forget.

|

|

Response 2:

|

|

Umaporn Jaisawang

2202235 Reading and Analysis in the Study

of English Literature

Acharn Puckpan Tipayamontri

January 7, 2009

Reading Response

SOS

George Henderson the lawyer declares of Mrs. Wright,

“I shouldn’t say she had the homemaking instinct”

(39), pronouncing her unfit to be a housewife by

looking at the house, and especially the kitchen, as

a reflection of the woman herself, to which Mrs.

Hale takes exception, “Seems mean to talk about her

for not having things slicked up when she had to

come away in such a hurry.” The set—“a

gloomy kitchen” (36)—and its setting—“down

in a hollow and you don’t see the road” (42)—then,

represent not only the absent suspect herself but

also her circumstance and even her state of mind.

That her voice and the kitchen are so closely

aligned as to be virtually one and the same thing is

illustrated in Mrs. Peters’ ease in fulfilling her

mission: “She [Mrs. Wright] said they [aprons] was

in the top drawer in this cupboard. Yes, here. And

then her little shawl that always hung behind the

door. (opens stair

door and looks) Yes, here it is” (40).

Everything is in its place. Therefore, when things

are not as they should be, which merely cause Mr.

Henderson to give unfair criticism, they should

cause the keener and more just observer to take

careful note. The women prove themselves to be

excellent listeners of Mrs. Wright (or great readers

of the text which is the set) and become properly

troubled and later alarmed.

The

prepared bread dough gives Mrs. Peters pause: “lift[s] one end of the towel

that covers a pan) She had bread set. (Stands still.)”

(39). The set speaks. That is, Mrs. Wright speaks.

And what the bread baking and dough being set to

rise say to the sheriff’s wife is that Mrs. Wright

was not planning on doing anything out of the

ordinary or on going anywhere where she cannot tend

to her cooking in progress. The set voices Mrs.

Wright’s innocent and normal intentions and plans.

“A loaf of bread beside the bread-box” tells Mrs.

Hale “She was going to put this in there” and

something disrupted her from completing the action.

From this normal lonely routine interrupted, the

women learn further from quilt sewing that began “so

nice and even” but ended “all over the place!” (41)

that Mrs. Wright thereafter becomes disturbingly “so

nervous.”

The

hinge “pulled apart” of a bird cage door (42) and a

canary with its neck wrung “wrapped up in [a] piece

of silk” (43) answer Mrs. Hale’s earlier demand

“What do you suppose she was so nervous about?”

(41). Questions are asked and the set responds. This

odd but natural conversation that these two women

have with the set in lieu of Mrs. Wright reveals an

isolated woman desperately starved of companionship.

In the language of kitchen things, homey chores, and

domestic use, Mrs. Hale is able to understand her

former friend’s distress signals and domestic abuse:

“She liked the bird. She was going to bury it in

that pretty box” (43), and finally come to her aid.

Like the canary that can still tell-tales even

through its broken neck, the set and setting give

Mrs. Wright’s testimony even though she is absent

and silent. You can hear it if you know how to look.

|

|

Study Question: Discuss

an intriguing conflict in the play. Who or what is involved in the clash,

and in what way? How is the difference, opposition, or contrast resolved,

or doesn’t it?

Response 1:

|

|

Khemika Pailinrat

2202235 Reading and Analysis in the Study

of English Literature

Acharn Puckpan Tipayamontri

January 7, 2009

Reading Response

Torn

Loyalties

Mrs. Peters might be seen as a minor character

compared to the central absent actor, Mrs. Wright,

and the outsize and outspoken farm wife, Mrs. Hale,

but the ironic title Trifles cautions us

that we ignore slighter things at our own peril, for

she embodies a crucial conflict in the play whose

outcome not only determines the fate of a tormented

woman but also defines her own independence from her

husband the sheriff, freeing two women with one

resolve as it were.

Unlike

Martha Hale, her fellow accomplice, Mrs. Peters does

not know Minnie Wright personally, making her a more

neutral jury member or judge. If anything, Mrs.

Peters, despite her sex, starts out defending the

men, “Of course it’s no more than their duty,” and

is predisposed to respect the legal system, “the law

is the law,” even if it is skewed against a woman or

women. That she changes her position from alignment

with her husband’s affiliation with the law or from

a noncommittal (even fearful [presumably of

wrongdoing]) bystander, “(in a frightened voice.)

Oh, I don’t know,” to a co-conspirator of a crime is

a remarkable about-face worth close attention.

This

is the conflict that turns the play. At the climax

of the story, Mrs. Peters is torn between loyalties.

Should she be loyal to her husband, who also happens

to be the sheriff and upholder of the law? Should

she be loyal to her sex, in the words of Mr.

Henderson, the county attorney? More specifically,

should she be loyal to her sense of wrong: “It was

an awful thing was done in this house that

night…Killing a man while he slept, slipping a rope

around his neck that choked the life out of him”? Or

should she be loyal to her sense of sympathy, of

human identification: “(in a whisper) When I

was a girl—my kitten—there was a boy took a hatchet,

and before my eyes—and before I could get there—(Covers

her face an instant.) If they hadn’t held me

back, I would have—(Catches herself, looks

upstairs, where steps are heard, falters weakly.)—hurt

him”?

The

play witnesses and displays Mrs. Peters’ struggle.

She becomes not merely herself but also an audience

surrogate, a proxy for viewers’ own debate within

themselves about what is right or wrong, who is a

criminal and who is not, whether it is possible or

acceptable that the law is not just, and the

paradoxical idea that committing a crime might be

the right thing to do. She swings between clashing

ideas: “I know what stillness is. (Pulling

herself back). The law has got to punish

crime.”

This

is the conflict whose resolution defies simple

classification and upturns several easy categories.

If it is difficult to judge whether Mrs. Wright is a

bad person or whether her act is supportable, it is

even more uncomfortable to say that Mrs. Peters is a

bad person or that her act is outright wrong.

Glaspell carefully makes it inconclusive. In

response to the county attorney’s suggestive

question that “a sheriff’s wife is married to the

law. Ever think of it that way, Mrs. Peters?” she

replies “Not—just that way.” The double meaning can

be taken as “not exactly,” disagreeing with the

remark, or as “not only that way,” arguing for more

than one definition or dimension of her identity:

she is not only a sheriff’s wife, or married to the

law, but also a woman, a person in her own right, an

upholder of other kinds of justice besides the

legal, and can be affiliated with other loyalties

like friendship and other kinship.

Mrs.

Peters’ final actions similarly straddle different

territories. “Suddenly Mrs. Peters throws back

quilt pieces and tries to put the box in the bag

she is wearing. It is too big. She opens the box,

starts to take the bird out, cannot touch it, goes

to pieces, stands there helpless.” On one

hand, her definite attempt to hide the incriminating

evidence is clear. On the other, she does not

actually do it, both because it is physically and

emotionally impossible for her to do so. Her silence

after Mrs. Hale’s closing words is another,

ironically, active choice that aids and abets the

withholding of proof of motive that would have made

a valid case against Mrs. Wright. Is she bad for

helping a murderer? It is intriguing to consider

that not doing something is doing something. To see

this “slight wiry woman” with “a thin nervous face”

as a lesser character is a serious underestimation

of her role in the play. Her wrenching sincerity in

grappling with opposing loyalties to eventually

favor a woman stranger she has just come to know in

half an hour through her kitchen is designed to

appeal to audience sympathy. She is the linchpin in

this astonishing conversion of theater goers into

conspirators. In the end, she is loyal to a sense of

justice that the law at that time does not and

cannot deliver. And the audience, inexorably,

becomes associated in this collusion.

|

|

| Links |

E-Text

Women's History

The Hossack Case

Productions

- Echo Theatre

(July 7–29, 2000)

- Sally Heckel, dir. A Jury of Her Peers

(1980)

|

Media

|

|

- Trifles, dir.

Mel Williams, Theater for a New Generation, New York

(2013; 25:35 min.)

|

|

- Trifles, dir.

Nancy Greening, D'Moiselles (2012; 22:42 min.)

|

|

- Trifles,

dir. Pamela Gaye Walker, Ghost Ranch Productions (2009)

|

|

- Trifles,

Jonathan Donald Productions

|

|

- Trifles, dir.

Brooke O'Harra, Two-Headed Calf (2010)

|

|

|

Reference

Glaspell,

Susan. Trifles. Plays.

Ed. C. W. E. Bigsby. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1987. 35–45. Print.

Further

Reading

Aarons,

Victoria. "A Community of Women: Surviving Marriage in the Wilderness."

Rendezvous 22.2 (1986) 3–11.

Print.

Alkalay-Gut,

Karen. "Jury of Her Peers: The Importance of Trifles." Studies

in Short Fiction 21.1 (1984) 1–9. Print.

Ben-Zvi,

Linda. "'Murder

She Wrote': The Genesis of Susan Glaspell's Trifles."

Theatre Journal 44.2 (1992):

141–62.

Ben-Zvi,

Linda, ed. Susan Glaspell: Essays on Her Theater

and Fiction. Ann Arbor: U of Michigan P, 1995. Print.

Gainor,

J. Ellen. Susan Glaspell in Context: American

Theater, Culture, and Politics, 1915–48. Ann Arbor: U of

Michigan P, 2007. Print.

Hernando-Real,

Noelia. Self and Space in the Theater

of Susan Glaspell. Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2011. Print.

Rajkowska,

Bárbara Ozieblo. Susan Glaspell: A

Critical Biography. Chapel Hill: U of North Carolina P, 2000.

Print.

Home

| Introduction

to the Study of English Literature | Literary

Terms | English Resources

|

Last

updated September 24, 2019